Blocky

Authors: Diane Horton (dianeh@cs.utoronto.ca) and David Liu (david@cs.utoronto.ca)

Description

A visual game in which players apply operations such as rotations to a recursive structure in order to work towards a goal. The main data structure is a quad-tree, so this assignment provides lots of practise with recursion and trees. Students also implement some interesting and challenging algorithms.

Game assignments may be less appealing to female than male students [1], so we designed a game that is puzzle-like, with simple rules, but that is challenging to play. We think the game board is attractive, bearing a resemblance to a Mondrian painting, and the colour scheme can easily be configured by students - this is surprisingly satisfying!

Metadata

| Summary | Students build a visual game that operates on a recursive structure. |

| Audience |

CS2.

Our implementation is in Python, with pygame for rendering, but the assignment could easily be adapted to another object-oriented language. |

| Difficulty |

The assignment is challenging but doable.

The starter code is substantial and

some of the algorithms are quite tricky, in particular:

To help students approach the assignment, we provide an extensive handout that breaks the work into a series of tasks, and offers a way to check correctness at each step. We ran this assignment very successfully in our CS2 with 450 students. Students had three weeks to complete the assignment and were allowed to work in pairs at their discretion. In addition to office hours and discussion board support, we devoted 30 minutes of class time to discussing the data structures and key algorithms when the assignment was released. Our students were very successful, on average earning 85% on the assignment. |

| Topics |

The primary topics covered are:

|

| Strengths |

The game is visually appealing

and students many enjoy showing it off to friends and family.

Thwarting your opponent's efforts to reach their goal

can be as fun as working towards your own goal.

It is fun also to watch two computer players of differing ability

compete against each other.

The coverage of recursion is thorough, with methods ranging from straightforward to difficult. We like that students implement some algorithms that require deep thought beyond just getting the recursion. Students experience a problem for which a dual representation (quad-tree and 2-D) is motivated. There are many non-trivial and critically important invariants and preconditions in the code. Because these are lifelines when students write the code, the value of carefully documenting code properties like invariants and preconditions becomes clear. All rendering code is provided, and all functionality can be autotested. A self-test is available for providing to students, and a full test suite is available for instructors. |

| Weaknesses | When applying an operation to the board, the code updates the rendering but does not animate the change. It can be difficult to see what happened. |

| Dependencies | The assignment assumes students are familiar with recursion, trees, and inheritance. |

| Variants |

Difficulty can be reduced,

while still leaving plenty of recursion,

by removing the goal to

create the largest connected blob

of a certain colour.

This eliminates the two most challenging algorithms:

converting to a 2-D representation, and

finding the largest connected blob.

The size of the assignment can be reduced by simplifying to

a one-player game without scoring.

Playing the game would be somewhat analogous to playing with a Rubik's cube.

Students could be asked to invent and/or implement new types of move. Possibilities include:

Students could be asked to invent and/or implement new types of goal. Possibilities include:

If an open-ended, exploratory task is appropriate, students can investigate the playability and difficulty of the game, perhaps even playtesting it. This could spark ideas for new move types and goal types. Students can invent and implement new algorithms for a smart computer player, or implement a known algorithm such as minimax. An undo operation could be added. If multiple undos are allowed, which would make sense in a solo game, this opens up a discussion about whether to store previous board states or previous operations, and the associated time-space tradeoffs. Students could turn Blocky into a game for the web or their phone by plugging in a different renderer class. |

The Game

Blocky is played on a randomly-generated game board made of squares of four different colours. We call the game board a "block." A block is either:- a square of one colour, or

- a square that is subdivided into 4 equal-sized blocks.

Each player is randomly assigned their own goal to work towards: either to create the largest connected "blob" of a given colour or to put as much of a given colour on the outer perimeter as possible.

There are three kinds of player moves:

- rotating a block (clockwise or counterclockwise),

- swapping the two halves of a block (horizontally or vertically), and

- "smashing" a block (giving it four brand-new, randomly generated, sub-blocks).

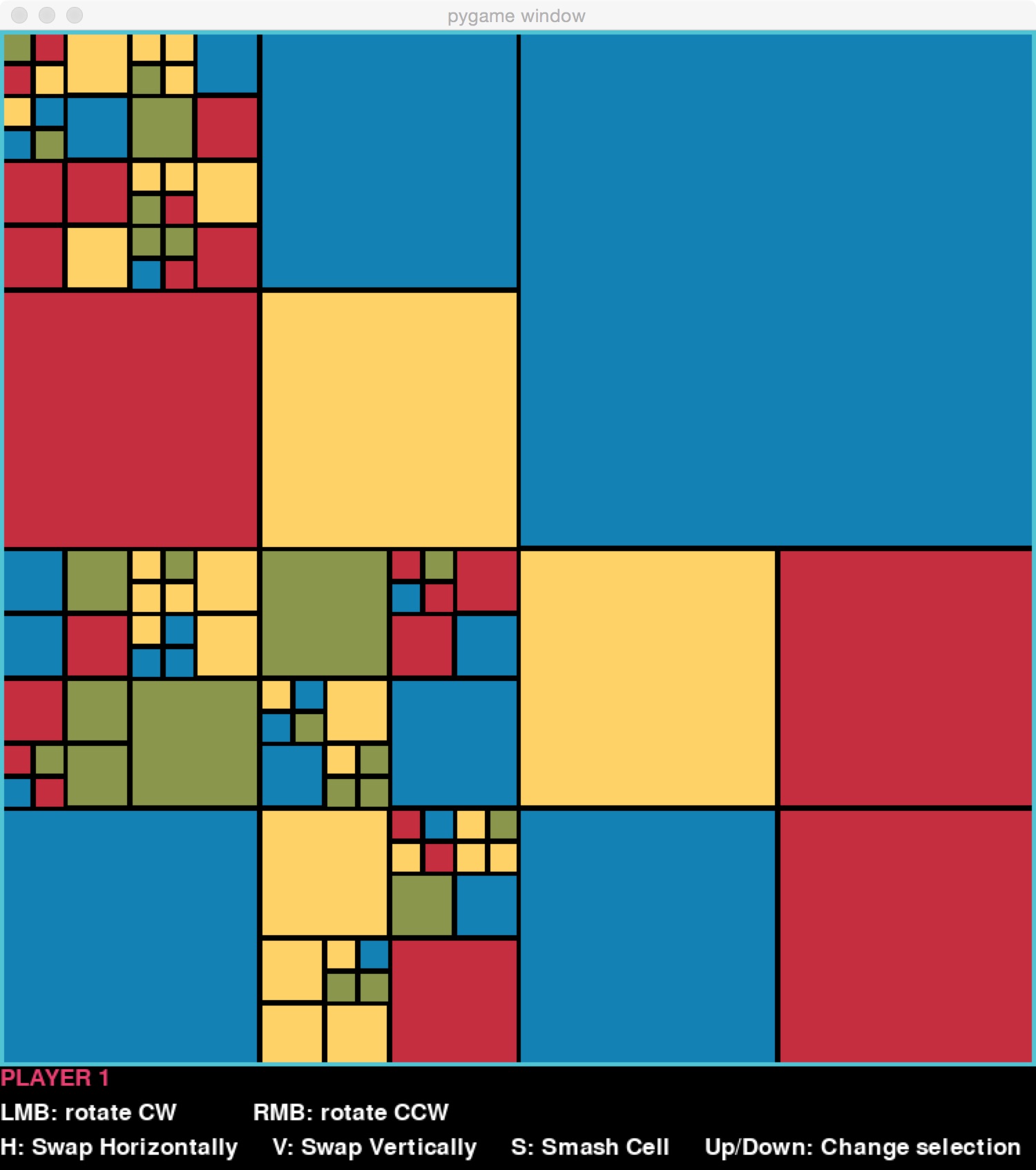

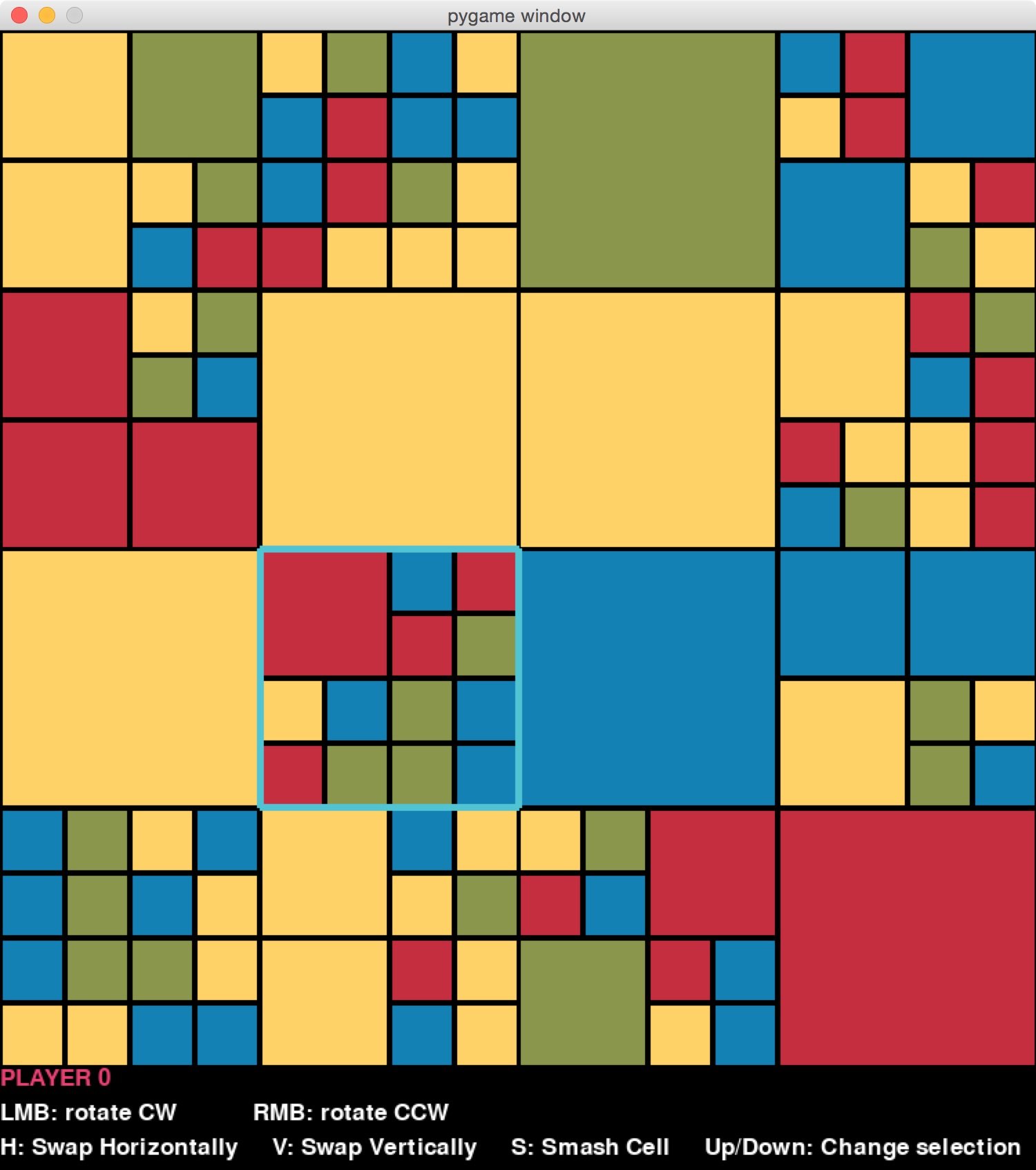

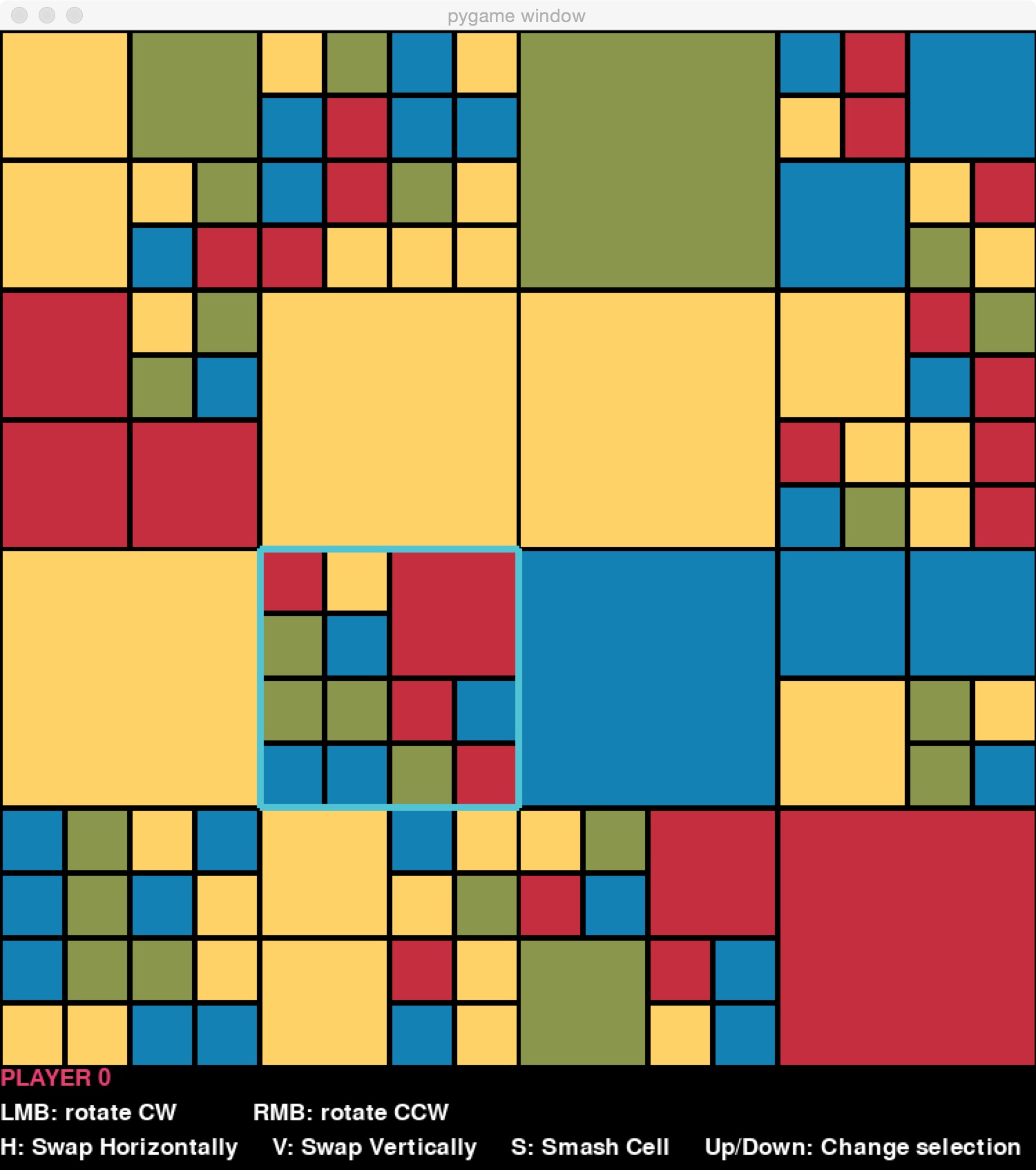

What makes moves interesting is that they can be applied to any block at any level. For example, on the board on the left below, the user has chosen a block (highlighted) that is two levels below the top level. Rotating it clockwise would result in the board on the right.

Data Structures

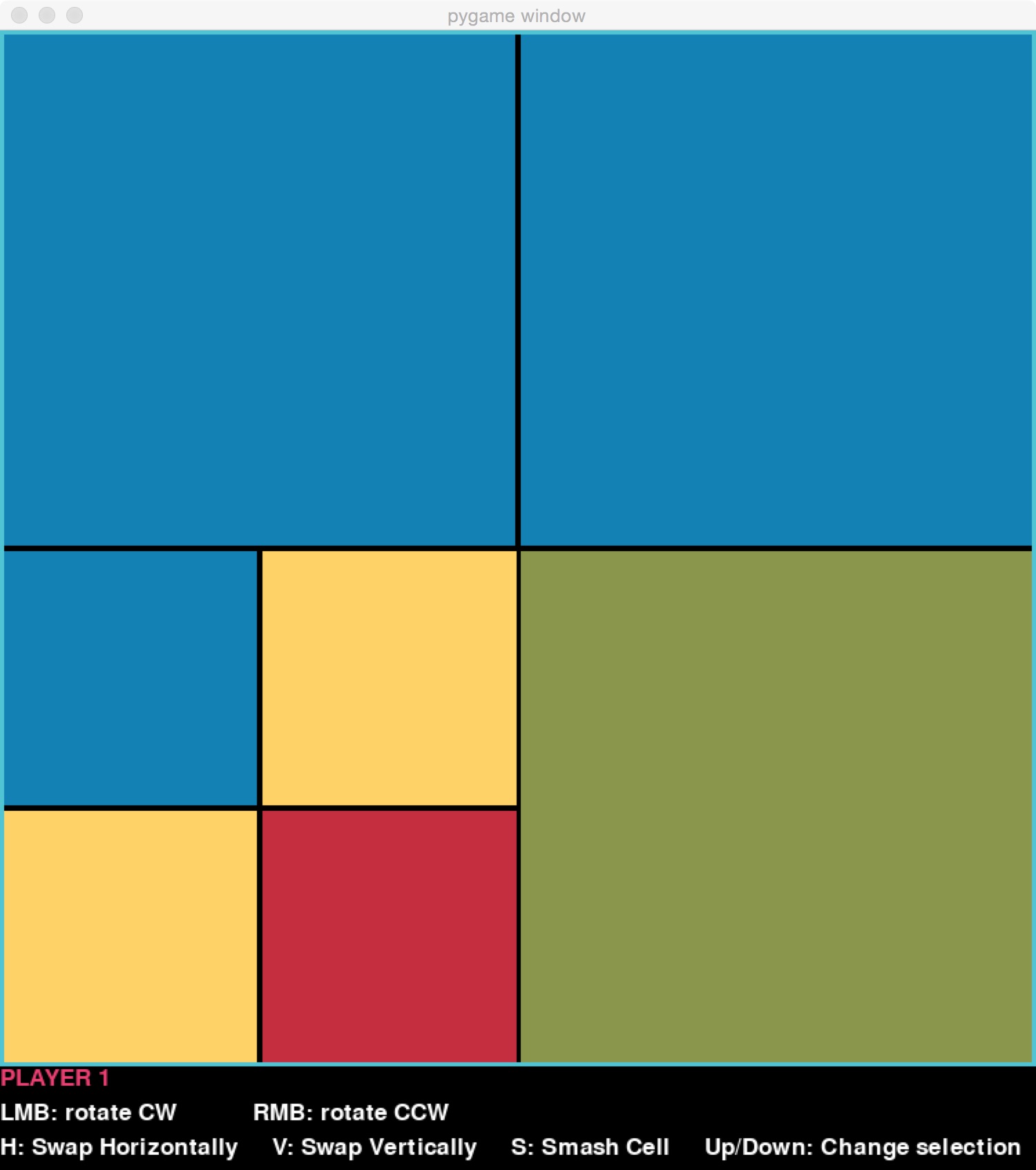

Blocks are represented using quad-trees. For example, suppose we set the maximum depth to just 2, and had this simple game board:

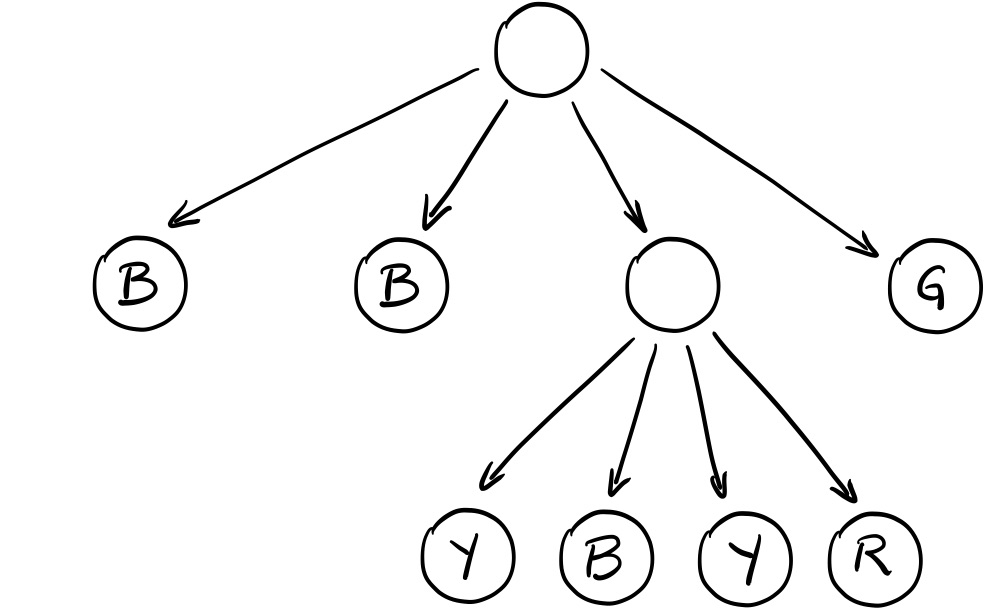

Its quad-tree would have this structure, where the children represent the upper-right, upper-left, lower-left, and lower-right sub-blocks, in that order:

- Each node has either 0 or 4 children.

- Only leaf nodes have a colour.

- If a node has children, their height and width is half of its height and width.

When scoring a player who has a "blob goal", we need to find the largest connected blob of the target colour. This is much easier to do on a 2-D representation than on a quad-tree, so students derive a 2-D representation from the quad-tree. The algorithm is tricky, because a block of uniform colour may need to be treated as 1 square, or 4 squares, or 16 squares, etc. depending on how finely divided the game board is. The board above, for example, is 4-by-4 in the 2-D representation, since a maximum depth of 2 allows the board to be divided into up to 16 squares. We implement the 2-D representation as a list of lists of colours.

Assignment Materials

- Handout

- Starter code

- Solution code is available upon request

- Self-test for students

- A full test suite is available on request

For the benefit of the community, we ask that adopters of the assignment do not post solutions or more of the starter code than we are providing here.