Keith Schwarz (htiek@cs.stanford.edu)

In this assignment, students use the debugger to explore and escape from mazes made of linked list nodes. In doing so, they learn to draw and interpret linked structures in memory purely using the debugger.

The starter files we give to students generates a maze out of four-way linked nodes that look like this:

| C++ | Java |

|---|---|

enum class Item {

NOTHING, POTION, SPELLBOOK, WAND

};

struct MazeCell {

Item whatsHere;

MazeCell* north;

MazeCell* south;

MazeCell* east;

MazeCell* west;

}; |

public class MazeCell {

string whatsHere;

MazeCell north;

MazeCell south;

MazeCell east;

MazeCell west;

} |

Addition: Jonathan Allen has provided a C# version available on github

There is no visualizer provided for the maze that's generated. Instead, students must use the debugger to explore the maze. They're looking for three items - the Wand, the Potion, and the Spellbook - which are scattered far away from the starting point.

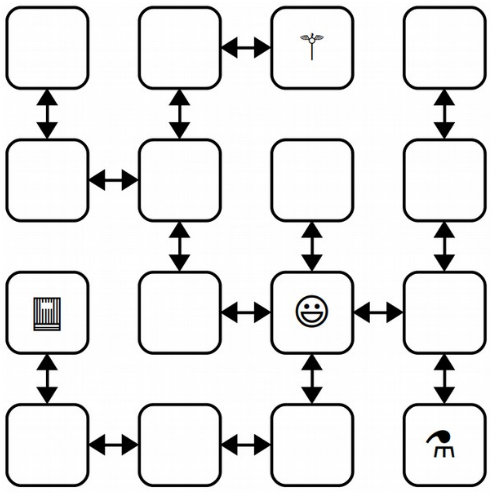

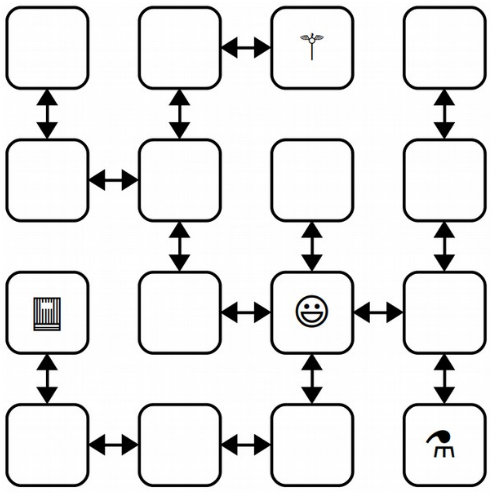

The assignment has two parts. In the first part, students explore a nicely-behaved, rectilinear grid maze that looks something like this:

We tell students to pull out a pen and paper and actually draw the maze as they explore it, helping them learn to diagram the contents of memory given just the debugger. Once students have finished this section, they'll know how to follow links between objects using the debugger and how to read the values of variables in memory (in particular, so they can see what items are at each point in the maze.)

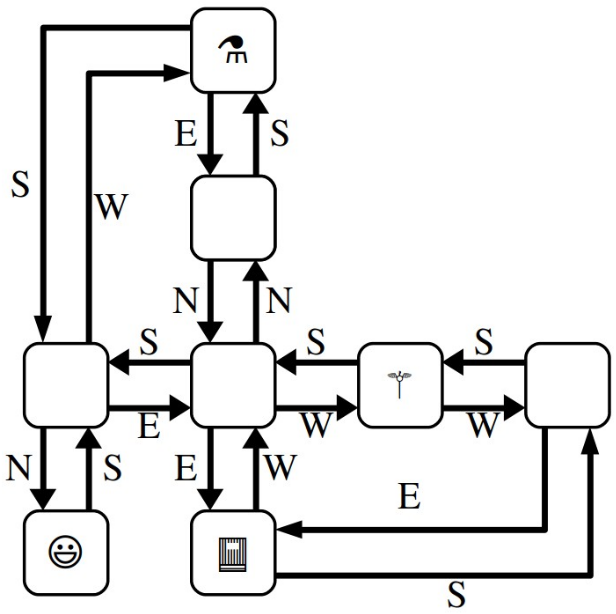

Once students have done this, we give them a second, more challenging maze that we call the "twisty maze." Twisty mazes look something like this:

There are still pointers labeled north, south, east, and west for each cell, but they no longer retain their traditional meaning. Completing this part of the assignment requires students to read the addresses of the MazeCell objects they encounter so that they don't find themselves going in circles. This also requires students to diagram memory in more detail than in the previous part of the assignment, since they need to remember the addresses of each object and which specific links they were following when moving from one location to another.

After finishing the assignment, students know how to pause a program and inspect memory in the debugger. They can read fields of objects. They can diagram on paper what linked structures look like in memory. They know how to read objects' memory addresses and find cycles in linked structures. And since all of this is framed in the context of a puzzle - find your way out of the maze - it can be used as a standalone exercise that's (in my opinion) a lot more fun that debugging broken linked list code. :-)

The assignment creates (with high probability) unique mazes for each student by using a hash of the student's name as a seed in the random generator that builds the mazes. This makes it possible for TAs to assist students in a sample maze (say, using the TA's own name) while still requiring the student to work through the exercise on their own. (This was inspired by the classic Binary Bomb assignment, which uses a similar technique.) To ensure that some students don't get "easy" mazes while others get "hard" ones, the items in the maze, and the starting location, are automatically placed as far away from one another as possible, ensuring that students need to do a decent amount of exploration.

The assignment deliverables are two strings of letters describing the sequence of steps through the two mazes that pick up all the items, which can easily be autograded.

| Summary | Students explore and escape a maze using the debugger. |

| Topics | Linked structures, debugging. |

| Audience | CS2, right around the time linked structures are first introduced. |

| Difficulty | Students didn't report much difficulty completing the assignment when we rolled it out last year. The difficulty can be adjusted by increasing or decreasing the sizes of the mazes, adding or removing items, or asking students to write the code that validates a path through the maze. |

| Strengths | This assignment turns working the debugger - usually a chore or something you do when your code isn't working - into a game. Rather than finding errors in code, it's about mapping things out and exploring. The fact that the mazes are personalized to each student also means that students can help teach one another how to navigate the mazes without giving away the full answers. |

| Weaknesses |

In the course of completing the assignment in C++, students never see pointers to deallocated memory or uninitialized

pointers, since the behavior across systems or runs of the same program are not consistent or predictable. This means that

students still can be confused by uninitialized pointers or pointers into freed memory when transitioning to later pointer

debugging. (The Java version doesn't have this issue. Thanks for being memory-safe, Java!)

In principle, students could solve this problem by using a BFS or a DFS to explore the full maze. We added in the three items to make this a bit trickier so that the path-of-least-resistance involves actually working the debugger. However, if this is used in a class that introduces these search algorithms beforehand, some very clever students might bypass the actual learning goals. |

| Dependencies | None; the maze generators can be built from scratch in most programming languages and all that's needed is a debugger. |

| Variants | This assignment could be adapted to work with mazes in which there are true dead ends (places you can enter but not leave) or, more generally, for any graph structure. |