CSC108H Assignment 2, Fall 2010

Due Wednesday 10 November, by 10:00 pm sharp!

There are no partners for this assignment.

Introduction

The purpose of this assignment is to give you more practice

writing functions and programs in Python, and in particular

writing code with strings, lists, and loops.

You should spend at least one hour

reading through this handout to make sure you understand what is

required, so that you don't waste your time going in circles, or worse yet,

hand in something you think is correct and find out later that you

misunderstood the specifications.

Highlight the handout, scribble on it, and find all the things

you're not sure about as soon as possible.

Authorship Detection

Automated authorship detection is the process of using a computer program

to analyze a large collection of texts, one of which has an unknown author,

and making guesses about the author of that unattributed text.

The basic idea is to use different statistics from the text

-- called "features" in the

machine learning community -- to form a linguistic "signature" for each

text. One example of a simple feature is the number of words per sentence. Some

authors may prefer short sentences while others tend to write sentences that go

on and on with lots and lots of words and not very concisely, just like this one.

Once we have calculated the signatures of two different texts we can

determine their similarity and calculate a likelihood that they were written

by the same person.

Automated authorship detection has uses in plagiarism detection,

email-filtering, social-science research and as forensic evidence in court cases.

Also called authorship attribution, this is a current research field and the

state-of-the-art linguistic features are considerably more complicated than

the five simple features that we will use for our program. But even with our

very basic features and simplifications, your program may still be able to make

some reasonable predictions about authorship.

We have begun a program that guesses the author of a text file

based on comparing it to a set of linguistic signatures.

Download find_author.py.

(Be sure to right click on the link in your browser so that you can use

"save as" rather than cutting and pasting the code.)

This program runs, but does almost nothing, because many of the functions'

bodies do little or nothing.

One symptom of this is that the program crashes if the

user types in any invalid inputs. In particular, it requests the name of a

directory (another name for folder) of linguistic signature files and expects the directory

to contain only those files -- more about that later.

Your task is to complete the program by filling

in the missing pieces.

An Overview: How the program works

The program begins by asking the user for two strings:

the first is the name of a file of text whose authorship is unknown

(the mystery file) and the second is the name

of a directory of files, each containing one linguistic signature.

The program calculates the linguistic signature for the mystery file and then

calculates scores indicating how well the mystery file matches each signature file in the

directory. The author from the signature file that best matches the mystery

file is reported.

Some Definitions: What really is a sentence?

Before we go further, it will be helpful to agree on what we will

call a sentence, a word and a phrase.

Let's define a token to be a string that you get from calling

the string method split on a line of the file.

We define a word to be a non-empty token

from the file that isn't completely

made up of punctuation. You'll find the "words" in a file by using

str.split

to find the tokens and then removing the puctuation from the words using the

clean_up function that we provided in find_author.py.

If after calling clean_up the resulting word

is an empty string, then it isn't considered a word.

Notice that clean_up converts the word to lowercase.

This means that once they have been cleaned up, the words yes, Yes and YES! will all be the same.

For the purposes of this assignment, we will consider a

sentence

to be a sequence of characters that (1) is terminated by (but doesn't include)

the characters ! ? .

or the end of the file, (2) excludes whitespace on either end,

and (3) is not empty.

Consider this file.

Remember that a file is just a linear sequence of characters,

even though it looks two dimensional.

This file contains these characters:

this is the\nfirst sentence. Isn't\nit? Yes ! !! This \n\nlast bit :) is also a sentence, but \nwithout a terminator other than the end of the file\n

By our definition, there are four "sentences" in it:

| Sentence 1 |

"this is the\nfirst sentence" |

| Sentence 2 |

"Isn't\nit" |

| Sentence 3 |

"Yes" |

| Sentence 4 |

"This \n\nlast bit :) is also a sentence, but \nwithout a terminator other than the end of the file" |

Notice that:

- The sentences do not include their terminator character.

- The last sentence was not terminated by a character;

it finishes with the end of the file.

- Sentences can span multiple lines of the file.

Phrases are defined as non-empty sections of

sentences that are separated by colons, commas, or

semi-colons. The sentence prior to this one has three phrases by our definition. This sentence right here only has one (because

we don't separate phrases based on parentheses).

We realize that these are not the correct definitions for sentences, words or phrases but using them will

make the assignment easier. More importantly, it will make your results match what we are expecting when we test

your code. You may not "improve" these definitions

or your assignment will be marked as incorrect.

Linguistic features we will calculate

The first linguistic feature recorded in the signature is the

average word length.

This is simply the average number of characters per

word, calculated after the punctuation has been stripped using the already-written

clean_up function. In the sentence prior to this one, the

average word length

is 5.909. Notice that the comma and the final period are stripped but the

hyphen inside "already-written" and the underscore in "clean_up" are both

counted. That's fine.

You must not change the clean_up

function that does punctuation stripping.

Type-Token Ratio is the number of different words used in a text

divided by the total number of words. It's a measure of how repetitive the vocabulary is.

Again you must use the provided clean_up

function so that "this","This","this," and "(this"

are not counted as different words.

Hapax Legomana Ratio is similar to Type-Token Ratio in that it is a ratio using

the total number of words as the denominator. The numerator for

the Hapax Legomana Ratio is the number of words occurring exactly once in the text.

In your code for this function you must not use a Python dictionary (even if you have already

learned about them on your own or are reading ahead in class) or any other

technique that keeps a count of the frequency of each word in the text.

Instead use this approach: As you read the file, keep two lists. The first

contains all the words that have appeared at least

once in the text and the second has all the words that have appeared at least twice in the

text. Of course, the words on the second list must also appear on the first. Once you've read

the whole text, you can use the two lists to calculate the number of words that appeared

exactly once.

The fourth linguistic feature your code will calculate is the average

number of words per sentence.

The final linguistic feature is a measure of sentence complexity and is

the average number of phrases per sentence. We will

find the phrases by taking each

sentence, as defined above, and splitting it on any of colon, semi-colon or comma.

Since several features require the program to split a string

on any of a set of different separators, it makes sense to write a helper

function to do this task. To do this you will complete the function

split_on_separators as described by the docstring in the

code.

Finding the Sentences

Because sentences can span multiple lines of the file, it won't work

to process the file

one line at a time calling split_on_separators

on each individual line.

Instead, create a single huge string that stores the entire file.

Then call split_on_separators on that string.

This solution would waste a lot of space

for really large files but it will be fine for our purposes. You'll

learn about algorithms that can handle large files in a future course.

There are other ways where our assignment design isn't very efficient. For example, having the

different linguistic features calculated by separate functions means that our program has to keep

going over the text file doing many of the same actions (breaking it into words and cleaning them up)

for each feature. This is inefficient if we are certain that anyone using our code would always

be calculating all the features. However, our design allows another program to import our module

and efficiently calculate a single linguistic feature without calculating the others. It also

makes the code easier to understand, which in today's computing environment is often more important

than efficiency.

Signature Files

We have created a

set of signature files for you to use

that have a fixed format. The first line of each file is the name of the

author and the next five lines each contain a single real number. These are values

for the five linguistic features in the following order:

- Average Word Length

- Type-Token Ratio

- Hapax Legomana Ratio

- Average Sentence Length

- Sentence Complexity

You are welcome to create additional signature files for testing your code and for

fun, but you must not change this format. Our testing of your program will depend

on its ability to read the required signature-file format.

Determining the best match

In order to determine the best match between an unattributed text and the known signatures,

the program uses the function

compare_signatures which calculates and returns a measure of

the similarity of two linguistic signatures. You could imagine developing some

complicated schemes but our program will do almost the simplest thing

imaginable. The similarity of signatures a and b

will be calculated as the sum of the

differences on each feature, but with each difference multiplied by a "weight" so

that the influence of each feature on the total score can be controlled. In other words,

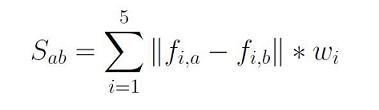

the similarity of signatures a and b (Sab) is the sum over all

five features of: the absolute value

of the feature difference times the corresponding weight for that feature.

The

equation below expresses this definition mathematically:

where fi,x is the value of feature i in signature

x and wi is the weight associated with feature

i.

The example below illustrates. Each row concerns one of the five features.

Suppose signature 1 and signature 2 are as shown in columns 2 and 3, and

the features are weighted as shown in column 4.

The final column shows the contribution of each feature to the overall sum,

which is 16.5.

It represents the similarity of signatures 1 and 2.

| Feature number |

Value of feature in signature 1 |

Value of feature in signature 2 |

Weight of feature |

Contribution of this feature to the sum |

| 1 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

11 |

abs(4.4-4.3)*11 = 1.1 |

| 2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

33 |

abs(0.1-0.1)*33 = 0 |

| 3 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

50 |

abs(0.05-0.04)*50 = .5 |

| 4 |

10 |

16 |

0.4 |

abs(10-16)*0.4 = 2.4 |

| 5 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

abs(2-4)*4 = 8 |

| SUM |

|

|

|

12 |

Notice that if signatures 1 and 2 were exactly the same on every feature,

the similarity would add up to zero. (It may have made sense to call this "difference" rather

than similarity.)

Notice also that if they are different on a feature that is weighted higher,

there overall similarity value goes up more than if they are different on a feature

with a low weight. This is how weights can be used to tune the importance

of different features.

You are required to complete function

compare_signatures

according to the docstring and you must not change the header. Notice that the list of

weights is provided to the function as a parameter.

We have already set the weights that your program will use (see the main block) so you

don't need to play around trying different values.

Additional requirements

-

Where a docstring says a function can assume something about a parameter

(e.g., it might say "text is a non-empty list") the function should not check that

this thing is actually true.

Instead, when you call the function make sure that it is indeed true.

-

Do not change any of the existing code. Add to it as specified in the comments.

-

Do not add any user input or output, except where you are explicitly told to.

In those cases, we have provided the

exact

print or raw_input

statement to use. Do not modify these.

-

Functions

get_valid_filename and read_directory_name

must not use any for loops, or they will receive a mark of zero.

The purpose of this is to make sure you get comfortable with while loops.

-

You must not use any

break or continue statements.

Any functions that do will receive a mark of zero.

We are imposing this restriction (and we have not even taught you these

statements)

because they are very easy to "abuse," resulting in terrible code.

How to tackle this assignment

This program is much larger than what you wrote for Assignment 1, so you'll

need a good strategy for how to tackle it. Here is our suggestion.

Principles:

-

To avoid getting overwhelmed, deal with one function at a time.

Start with functions that don't call any other functions; this will allow

you to test them right away. The steps listed below give you a

reasonable order in which to write the functions.

-

For each function that you write, plan test cases for that function and

actually write the Python code to implement those tests before you

write the function.

It is hard to have the discipline to do this, but you will have a huge

advantage over your peers if you do.

-

Keep in mind throughout that any function you have might be a useful helper

for another function.

Part of your marks will be for taking advantage of opportunities to call an existing

function.

-

As you write each function, begin by designing it in English, using only a few

sentences. If your design is longer than that, shorten it by describing the

steps at a higher level that leaves out some of the details.

When you translate your design into Python, look for steps that are described at such

a high level that they don't translate directly into Python.

Design a helper function for each of these, and put a call to the helpers into

your code.

Don't forget to write a great docstring for each helper!

Steps:

Here is a good order in which to solve the pieces of this assignment.

-

Read this handout thoroughly and carefully, making sure you understand everything

in it, particularly the different linguistic features.

-

Read the starter code to get an overview of what you will be writing.

It is not necessary at this point to understand every detail of the functions

we have provided in order to make progress on this assignment.

-

Create a module called

function_tester.py and have it import

your find_author module.

Add a main block to function_tester: that is where you can

put your code that tests your individual functions. For now, it can just

say pass.

-

Plan testing for, write, and test function

get_valid_filename.

In order to determine whether a file exists or not,

use the function os.path.exists.

Give it a string that is the name of a file, and os.path.exists

will return a boolean

indicating whether or not the file exists.

The help for this function talks about giving it a path

(which is a description of the file and where it exists

among all your folders),

but if you give it a string that is simply a file name, it will check in

the folder in which your code is running.

-

Plan testing for, write, and test function

read_directory_name.

Use the function os.path.isdir to check if a string is a valid

directory.

-

Plan testing for, write, and test functions for the first three

linguistic features:

average_word_length,

type_token_ratio, and hapax_legomana_ratio.

-

Write, and test function

split_on_separators.

Test this function carefully on its own before trying to use it in your other

functions.

-

Write and test function

average_sentence_length.

Begin by writing code to extract the sentences from the file. Test that this part of

your code works correctly before you worry about calculating the average length.

-

Complete

avg_sentence_complexity and finally compare_signatures.

-

Now you have implemented all the functions.

Run our

a2_self_test module to confirm that your code passes

our most basic tests.

Correct any errors that this uncovers.

But of course if you did a great job of testing your functions as you wrote

them, you won't find any new errors now.

-

You are now ready to run the full author detection program:

run

find_author. To do this you will need to set up a

folder that contains only valid linguistic

signature files. We are providing a set of these on the

data files page You'll also want some mystery text files

to analyze. We have put a number of these on the

data files page.

If you are copying them to your home machine, don't put them in the

same folder as the linguistic signature files.

Testing your code

We are providing a module called

a2_self_test

that imports your find_author and checks that

most of the required functions

satisfy some of the basic

requirements.

It does not check the two functions that involve input and output

with the user: get_valid_filename and

read_directory_name.

When you run a2_self_test.py, it should produce no errors and its output

should consist only of one thing: the word "okay".

If there is any other output at all,

or if any input is required from the user,

then your code is not following the assignment specifications correctly

and

will be marked as incorrect.

Go back and fix the error(s).

While you are playing with your program,

you may want to use the signature files and

mystery text files we have provided.

This in conjunction with

a2_self_test is still not sufficient testing to

thoroughly test all of your functions under all possible

conditions.

With the functions on this assignment, there are many more possible cases

to test (and cases where your code could go wrong).

If you want to get a great mark on the correctness of your functions,

do a great job of testing them under all possible conditions.

Then we won't be able to find any errors that you haven't already fixed!

Marking

These are the aspects of your work that we will

focus on in the marking:

-

Correctness: Your code

should perform as specified.

Correctness, as measured by our tests, will count for the

largest single portion of your marks.

-

Docstrings: For each function that you design from scratch,

write a good

docstring.

(Do not change the docstrings that we have already written for you.)

Make sure that you read the Assignment rules page for some important

rules and guidelines about docstrings.

-

Internal comments: Within

functions, the more complicated parts of your code should also be

described using "internal" comments.

For this assignment, internal comments will be more important

than on assignment 1.

-

Programming style: Your variable names should be meaningful and

your code as simple and clear as possible.

-

Good use of helper functions: If you find yourself repeating a task, you should add

a helper function and call that function instead of duplicating the

code.

And if a function is more than about 20 lines long, consider introducing

helper functions to do some of the work -- even if they will only be called once.

-

Formatting style: Make sure that you read the Assignment rules page for some important

rules and guidelines about formatting your code.

This assignment will be completed on your own without a partner.

You must hand in your work electronically, using the MarkUs online system.

Instructions for doing so are posted on the Assignments page

of the course website.

For this assignment, hand in just one file:

Once you have submitted, be sure to check that you have submitted

the correct version; new or missing files will not be accepted after

the due date.

Remember that spelling of filenames, including case, counts.

If your file is not named exactly as above,

your code will receive zero for correctness.

Future Thoughts

If you carefully examine the mystery files and correctly code up your assignment, you'll

see that it correctly classifies many of the documents -- but not all. Some of the linguistic features

that we have used (type-token ratio and hapax legoamana ratio in particular) are standard techniques,

but they may not be sufficient to do the classification task. There are other standard features

and more sophisticated techniques that were too complicated for this assignment. Suppose

you could use a Python dictionary to keep a count of how many times each word appeared

in a document. What new linguistic features would that allow you to use?

Some authors like to use lots of exclamation marks!!! or perhaps

just a lot of punctuation?!

Could you devise a linguistic feature to measure this? While this is fun to think about,

do not add any different linguistic features to the version of the program that you

submit for marking.

Another area for thought is how authorship attribution is related to plagiarism

detection. In this

TIME magazine article, plagiarism detection software is used to support the claim

that Shakespeare was the author of an unattributed play.

In the field of machine learning (of which authorship detection is a subfield), programs

often learn their own configuration values through training.

In our case, could the program learn from trying to guess an author and

then being told the right answer? Could it learn to adjust the weights

being applied to the different features? What about learning a new feature? How would

you do this?